The Restaurant Resistance

A little historic inspo

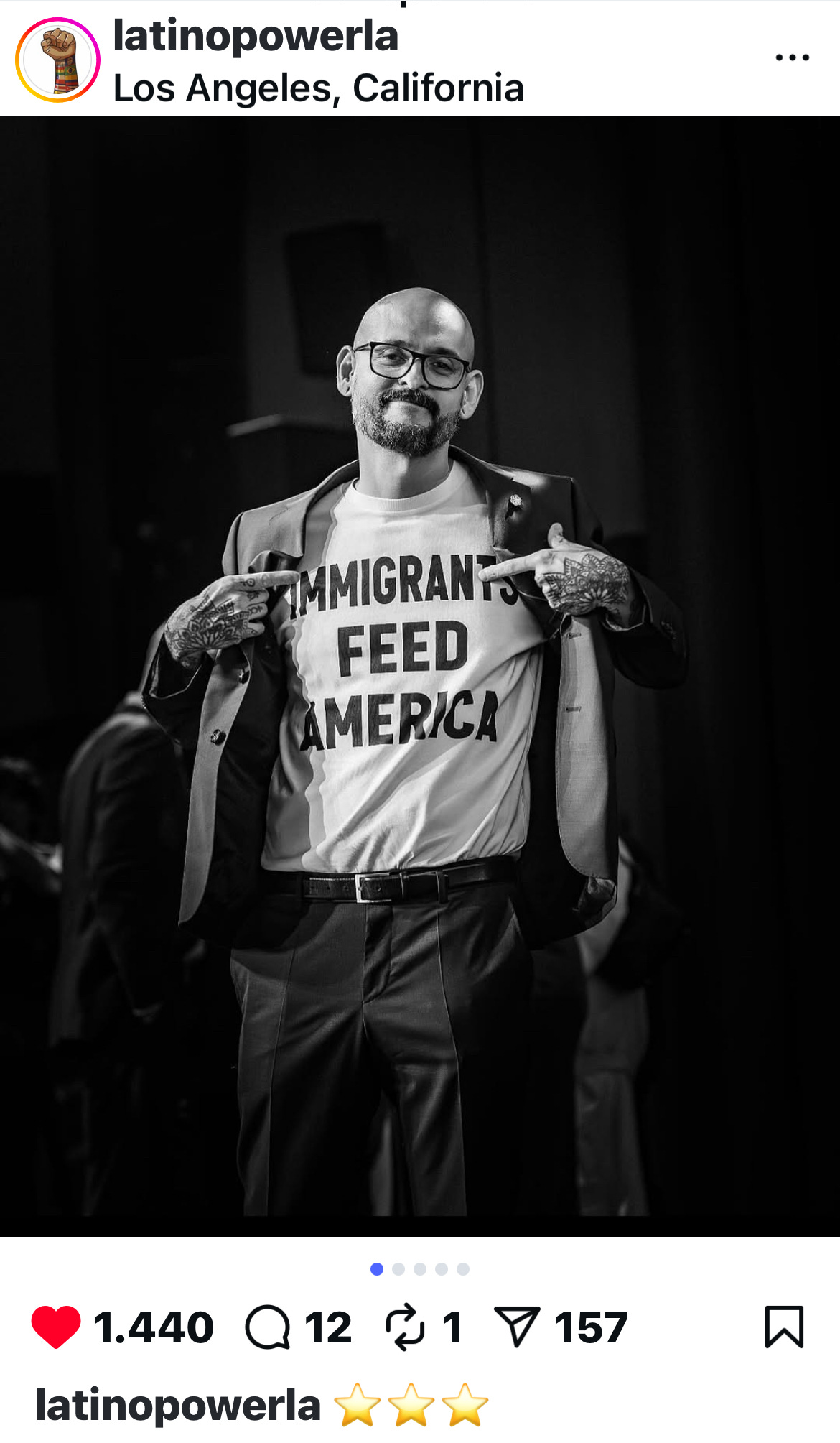

At one of the highest points of his career, chef Aitor Zabala chose to make a statement. As he stepped onto the stage this past June to don the Michelin chef’s jacket that signalled that his Los Angeles restaurant, Somni, had just been awarded three stars, Aitor, who was born in Spain, turned to the audience, and gestured triumphantly to his t-shirt. It was emblazoned with the words ‘Immigrants Feed America.’

That t-shirt (which echoed one that fellow Spaniard José Andrés had worn to the 2019 State of the Union address) may have seemed like a small gesture. But in the current wave of raids, detentions, and extrajudicial deportations directed against immigrants and that have hit the US restaurant industry–where a little more than 1 in 5 workers were born outside the country–with brutal force, even a small act of resistance can inspire others. At a time in which so much is at risk, and in which so many feel overwhelmed and fearful (for their jobs, for the businesses they have built, for their families, their neighbors, for their own well-being, for democracy itself), even a small act can remind others that they are not alone, or helpless.

So we thought we’d take the occasion of this newsletter to provide some context. To remind our readers of this industry’s history of resistance, and how, in gestures both large and small, it has in the past said no to injustice and authoritarianism.

In truth, food has always functioned as a form of resistance. From the Africans who carried recipes and seeds with them when forced aboard transatlantic slave ships, and thereby kept their culture from being eradicated in the harsh new world in which they landed; to the ollas communes–or collective kitchens–that spontaneously emerged to feed Chile’s most vulnerable following the 1970s coup (and that were so threatening to the newly installed dictatorship that the Pinochet regime labelled them a terrorist organization); to all of us today who try to eat locally and support regenerative agriculture as a means of rejecting the various forms of damage caused by industrial food production: what we put in our mouths can be an important means of critiquing, rejecting, and in a few cases even overthrowing those in power.

The French Revolution

A case in point: It’s safe to say that there would be no French Revolution had women in Paris’s markets not started rioting over the high price of bread one October morning in 1789, then marched to Versailles to make sure the king knew of their displeasure. But you know what else historians agree contributed to the Revolution?

Coffee houses. Paris got its first–Le Procope, still in existence—in 1686, and it and the others that followed quickly became favored hangouts for smart people with things to say (including a few with names like Locke and Rousseau), to exchange news, and to discuss limiting absolute monarchy and shit. Coffee houses, in other words, provided the space for the exchange of critical thinking and revolutionary ideas that we know of today as The Enlightenment.

Italy under Fascism

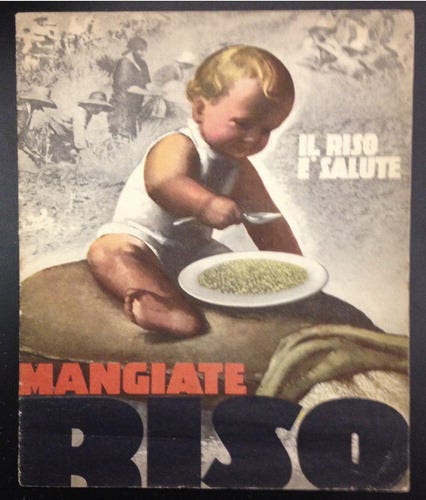

In one of the truly more insane measures of Italy’s Fascist government, Mussolini attempted–we are not making this up–to ban pasta. His reasons were partly economic; Italy did not produce enough wheat to meet its needs, and il Duce wanted to reduce reliance on foreign imports and boost homegrown rice production instead. But there were also ideological concerns.

Fascism was inspired by the artistic and social movement known as Futurism, whose leader, Tommaso Marinetti, wrote a Manifesto of Futurist Cuisine that blamed pasta-eating for causing “weakness, pessimism, nostalgic inactivity and neutrality”--in other words, for converting Italy’s manly men into a bunch of lazy sadbois unable to get off their mamma’s couch because their tummies were too full. Luckily, the far more reasonable women of southern Italy were having none of it, and protested the proposed ban, so the Fascists had to content themselves with pro-rice propaganda instead.

Once the Second World War broke out, Italian farmers were required to turn over their crops and other production to the state. Both out of self-preservation and as a form of resistance, many illegally withheld part of their production from the regime. So when Mussolini was deposed and arrested in July 1943, and Italians mistakenly believed the war was over, the seven Cervi brothers of Emilia Romagna were able to break out their stash of flour, scrounge up some butter and cheese from local dairies, and invite everyone in town to celebrate with 380 kilos of ‘pastasciutta’ or ‘dry pasta’. To this day, Italians annually celebrate the day that Mussolini fell, with communal pastasciutta antifascista dinners. It’s on July 25, should you want to join.

Europe under the Nazis

There’s a reason that Casablanca was set in a nightclub, and it wasn’t just to provide Humphrey Bogart with a steady supply of alcohol. Restaurants, cafés, and bars in Europe and North Africa functioned as important hubs for the resistance against the Nazis, providing meeting places, safe houses, and storage for supplies and weapons. At Café Gondrée in occupied Normandy, the French owners, unbeknownst to the German officers who hung out there regularly, were members of the Resistance. Wife Thérèse spoke Alsatian, so she could understand what the German officers were saying; she would tell her husband Georges, who spoke English and would transmit the intelligence to British agents in the area. After the D-Day landings, the couple and their two young daughters became the first French family to be liberated. Their café, renamed the Pegasus Bridge Café, is still in business.

The owner of Cafe Smolders in The Netherlands helped disgruntled German soldiers defect; Frituur de la Bourse in Brussels was a meeting place for the Belgian resistance; the Hotel Montholon in Paris (still in existence!) provided accommodation for the members of the lines that helped citizens escape from occupied territory. The owners of the Martutene pub outside San Sebastián would take care of downed Allied airmen who managed to escape over the Pyrenees and get them to the British embassy. And in Copenhagen, a member of the Danish Resistance assassinated a Nazi snitch at Rosengårdens Vinstue (also still around; the bar’s slogan ‘a shot for a shot’ describes its practice of showing the bullet hole to anyone who indulges in a slug of Gammel Dansk).

It wasn’t just restaurateurs. Winemakers throughout occupied France hid their best bottles from the Nazis, sometimes even slapping good labels on plonk and figuring the barbarians wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. Others fought back in more serious–and dangerous–ways. With his vineyard close to the demarcation line between the Nazi-controlled north and the puppet Vichy regime in the south, wine grower and négociant Jean Monmousseaux frequently had to cross the border with wine shipments—which conveniently allowed him to stuff some of his barrels with weapons and actual Resistance fighters. In Champagne, some of the great houses transformed their crayères–the 2000-year-old chalk caves where they stored their bottles–into secret weapons depots for the Resistance that would help arm the Allies on D-Day.

In Marseille, which remained unoccupied until late in 1942 and, thanks to an underground workshop that forged documents, became the city to go to if you were trying to get an illegal exit visa, a group of artists, intellectuals, actors, and political activists who gathered regularly at the café Bruleur du Loup hatched a scheme to start a secret food cooperative. The fruit-and-nut bars they produced from the dates and almonds still arriving in Marseille’s port didn’t fall under rationing restrictions, so the coop could sell them in tobaccoists and boulangeries throughout the city, providing a sort of cheap energy bar for a population that was already suffering reduced food supplies and a salary for the refugee-workers it employed. For one of the Cooperative des Croque-Fruits’ founders, an actor who was also the organization’s leading salesman, distributing the bars gave him the perfect alibi for his other work: handing out political leaflets and secretly promoting the resistance.

Even the Michelin guide contributed to the Allied war effort, allowing the US Army to reprint the detailed maps (though not, presumably, its recommendations; the military probably didn’t want anyone taking a detour, no matter how worthy) from its 1939 guide and distribute them to Allied commanders to help them navigate their troops eastward from the Normandy beaches.

Russian Invasion of Ukraine

Within days of Russia invading Ukraine in February 2022, chefs like Ievgen Klopotenko had converted their restaurants into canteens to feed both citizens and soldiers, and their kitchens into occasional bomb shelters. Others, like chef and food writer Olia Hercules, who is based in London, launched crowdsourcing initiatives to raise money for Ukraine. Still others, like Private Breus, a former chef at Kyiv’s well-regarded Veranda and one-time participant on Master Chef Ukraine, simply enlisted and kept cooking–this time for his fellow soldiers.

Klopotenko and other chefs also enacted a stunning bit of cultural resistance: he launched an international campaign to get the cooking of borsch, a soup that Russia would like to claim as its own, inscribed on UNESCO’s cultural heritage list. In June 2022, the UN agreed, and gave it protected status.

And… today?

There have been some efforts within the industry in the US to resist the roundups and deportation of immigrants, and to protect staff from the administration’s crackdown. A lot of these are kept quiet, out of fear of attracting unwanted attention. But in Chicago, for example, one bagel shop owner closed the doors of his restaurant but continued to sell bagels out the window so that staff members who didn’t feel safe coming into work could stay home. In the same city, as well as in Washington DC (and probably elsewhere), some industry people have started closed chatgroups on Telegram and Signal to share intel about raids and legal advice. In Denver, Tiffany Hernandez, a bartender and founder of Escuelitas, has been offering Know Your Rights courses for employees.

In Los Angeles, Javier Cabral, the editor of LA Taco, (who will be moderating our MAD Monday on Borders next week!), has reported on some mom-and-pop places that have locked their doors and done service from a window in order to protect their staff. And he sees the introduction of a weekly “Rustic Cantina” night at the fine dining Rustic Canyon as a way for executive chef Jeremy Fox to platform Mexican culture and, more specifically, his head-chef, Elijah Deleon. But he’s been disappointed, he says, that the restaurant community in LA hasn’t been more outspoken.

“I’ve spoken to owners off the record, and they’ll say things like ‘our attorney warned us against speaking out or posting anything because ICE is using social media to target places,” he says. “The more quiet you are, the less likely you are to be targeted.”

He understands why speaking out is a daunting prospect. “I’m not going to tell someone how to do their job or how to protect their workers,” he says. “And I know that some people want to play it safe because it’s a really tough time for restaurants in LA: a lot of places are closing because people aren’t going out to eat, because of the recession, because of the fires, because of immigration sweeps.”

But as someone who “grew up in the East-LA backyard punk scene,” Javier says, he wishes more people were taking public action. “I’d like to see more clear and direct protection from restaurants all over LA to support the working backbones of their restaurants,” he says. “The ones who have had their backs for so long.”

Are you seeing acts of resistance where you are? Let us know in the comments

WHAT WE’RE UP TO

MAD Monday LA

Join us on November 10th for a conversation about borders and what brings us to the same table. Perhaps it’s a recipe passed through generations, a spice from across the world, or a dish that tastes like home to people from different places.

We’ll explore how our global food system has grown richer through movement, migration, and exchange with speakers Sana Javeri Kadri (founder of Diaspora Spice Co.), Lulu Wang (writer/director of The Farewell and Expats), Anthony Wang (chef/owner of firstborn), and Javier Cabral (editor-in-chief of L.A. Taco). The day includes coffee and a light lunch from Manuela.

Tickets for MAD Monday LA have sold out, but join our waiting list here to be notified if spots open up or for future events.

Taste Buds 2026

Our friends at Noma Projects have opened enrollment for their membership club Taste Buds 2026. And they’ve got a special offer for MAD Digest subscribers.

Taste Buds is how the noma team shares the things too new, too fleeting, and too incredible to stay locked in the kitchen with curious people around the world. Members get a quarterly delivery of limited products from the Test Kitchen, Fermentation Lab, and noma vault. Taste Buds also have a direct line to the noma team’s expertise through recipes, a dive into the weird and wonderful world of fermentation at home, and the chance to opt into access to member-only events.

Use the code MAD50 for €50 off your membership.