When It Happens To You

Two chefs, two continents, one climate emergency. Plus MAD alum Harriet Tomlinson on fixing her inner compass, and more MAD7 Symposium news

LONG READ

When It Happens To You

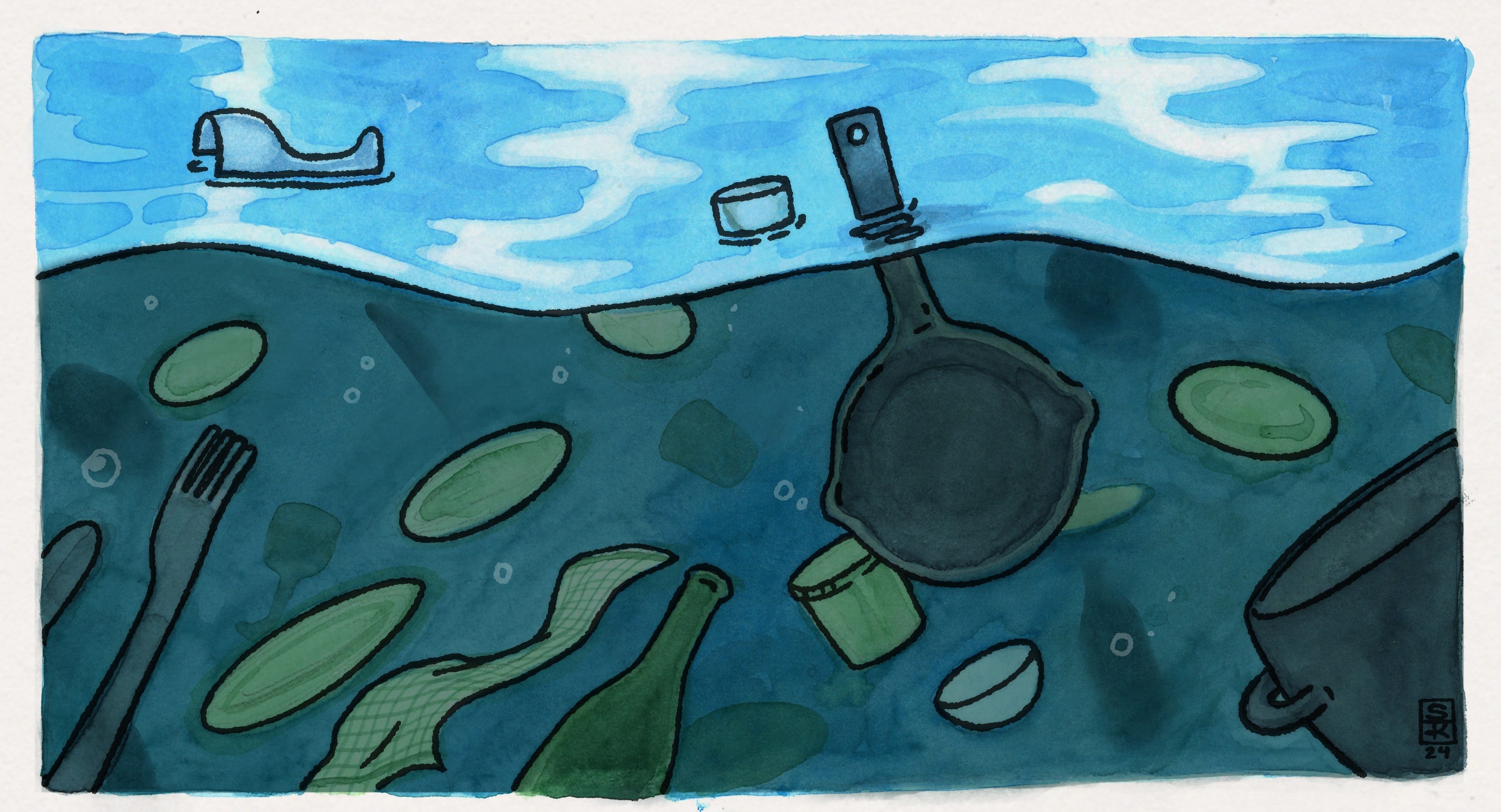

“It was surreal,” says chef Katie Button of the hurricane that flooded her city of Asheville, North Carolina in late September, knocking out the local water supply for 53 days, destroying countless homes and businesses, and killing over 100 people. Half a world away, chef Ricard Camarena reaches for the same phrase when he tries to describe the violent storm that dropped a year’s worth of water in four hours in his home province of Valencia, Spain, reduced dozens of towns to little more than muck and rubble, and left over 200 people dead. “Fue algo surrealista.”

Separated by an ocean and two very different cultures, the word that Katie and Ricard each spontaneously chose to describe an unprecedented disaster reflects the deeper experience they now share. Both of them are still coming to grips with the impact of extreme weather devastation on their communities. Both of them found a meaningful way to help by doing the thing that they do best, which is to cook. And although neither of them ever doubted the reality of climate change, they both have now reached a new, realization about it that can only come from experiencing it for yourself: it can happen to anyone.

The restaurant industry is supremely vulnerable to climate change. Rising temperatures are already affecting the supply chain, disrupting agricultural production and distribution, and driving up food prices around the world. According to a report published this year by the James Beard Foundation and the Good Food Institute, that trend will continue, and is expected to diminish revenues across the industry beginning in 2027. But it’s the climate-related natural disasters–the wildfires and droughts and hurricanes and, yes, floods— that will have the greatest impact. By knocking out infrastructure, disrupting distribution, destroying crops and buildings, halting tourism, and upending economies, they pose nothing short of a full-on, existential threat.

In truth, both Katie and Ricard were lucky. In the latter’s case, his eponymous restaurant is located in the city of Valencia, which was spared the devastation that hit dozens of surrounding towns. “It was like a miracle,” he says. “In one part, it’s as if a tornado has come through, and in the other, it’s like nothing happened.”

For Katie, it was significantly more complicated. When the storm struck early on the morning of Sept 27, taking down dozens of trees and knocking out power and cell phone service, she was at home. “We literally couldn’t communicate with anyone, and we couldn’t get any news, so we didn’t know how bad it was,” she says. It wasn’t until Sunday that she knew that her entire team was safe, and by then it was clear that entire neighborhoods were just, as she puts it “gone.” But the center of the city, where her restaurants Curaté and La Bodega are located, was mostly spared, and over the course of that weekend, they regained power. Water, however, was another story: the storm had taken out the local reservoir.

Both chefs leapt into action to help the affected in their respective communities. In Katie’s case, it started with a call from World Central Kitchen, the nonprofit organization founded by José Andrés that activates restaurants to feed people during times of disaster. “We had power by then, so we could cook for people,” Katie says. “And WCK was amazing. They got us a water tank. They handled all the logistics, they connected us with restaurants that had food in their walk-ins that had to be used, and they brought in cars and trucks and even helicopters to distribute the food. And they pay you per meal, which meant—the company had been forced to furlough everyone— we could bring some of our people back to work.”

Still, a key irony wasn’t lost on her: “We had held so many fundraisers for WCK in the past. It was surreal to be on the other side of it.”

In Ricard’s case, it took a day or so after the storm hit on Oct 29 before news of what had happened in towns that were now effectively cut off from the outside world, even though they were just a few kilometers from the capital of Valencia. But once he saw the images coming out of places like Cheste and Paiporta, he knew he had to act. “By the 1st, we saw that there was an emergency, because there wasn’t food in the pueblos. So we started cooking.”

Ricard contacted the meat production facility that prepares the restaurant’s charcuterie, and asked if they could repurpose the place as a temporary canteen. Together with his wife Mari Carmen, they organized suppliers and staff so that, within hours, 80 people were at work in the factory preparing meals, while employees who lived in the affected towns organized private brigades of vans to pick up food and then distribute it. By the end of the first day, they had distributed 10,000 meals. Soon, they would be up to 25,000 a day.

“When it first occurred to me that we should be cooking on a large scale for these people, I remember thinking, ‘Oh, I wish I was the government, and had an enormous place to cook, with the resources to get the food out to everyone,’” Ricard says. “And then I realized, maybe I do have it. It turns out many times that you have the capacity, even if you don’t realize it at first.”

He and Mari Carmen didn’t stop there. Together with his colleagues Quique Dacosta and Begoña Rodrigo, Ricard quickly set up a fund for donations, called Desde Valencia Para Valencia and asked colleagues across Spain and around the world to hold dinners to raise money for it. Hundreds have agreed, with many joining together for collaborative fundraising dinners on December 13, and others donating a table or a service from their restaurant on another night. The goal is to raise 100 million euros for small businesses affected by the storm.

As grateful as they are for their own relative fortune, and for the opportunity to help others who weren’t as lucky, both chefs have seen their businesses affected by the respective disasters, and their trust in the system eroded. In Ricard’s case, tourism has dropped off significantly in Valencia, even though the capital proper wasn’t affected by the storm.

That’s been true for Asheville as well–so much so that Katie’s companyclosed La Bodega indefinitely, because there weren’t enough tourists to support two restaurants. They’ve had to permanently lay off 30% of their team. And even though they were able to open about two or three weeks after the storm thanks to that water tank that WCK got them, the financial hit has been severe.

“We still had to buy water for prepping and cooking,” Katie says. “We served on paper plates and hauled water up from the creek behind the restaurant to flush the toilets. But it cost us $1000 a day to buy our own water.”

The experience has left both chefs deeply disillusioned with the systems they thought were in place to protect people in just this kind of situation. The Curaté group had insurance that they believed covered everything, only to learn–45 days after they filed their claim–that there were a lot of exceptions. “When you do not have water for 53 days, your business is seriously impacted,” Katie says. “You pay for business interruption insurance, and you think it covers whatever it takes to make you whole again, especially in a hurricane. But there are 300 pages of fine print that remove every layer of protection. It can feel fraudulent.”

She has been even more appalled to learn that the government doesn’t regulate the insurance industry tightly enough to prevent that kind of misrepresentation. Ricard is just appalled at the government response in general. “It’s a disgrace,” he says. “There were towns six kilometers from Valencia that eight or nine days later, still hadn’t seen a single firetruck or police officer-–they were completely abandoned by the administration.”

For both chefs, the experience has been a wakeup call, a direct lesson in the kind of havoc that climate change can wreak, and a powerful reminder that its reach does not discriminate. “You think these things only happen in remote places,” Ricard says. “Not outside a big city in Spain.”

Katie understands the sentiment. Like most of us, she had managed to lull herself into thinking that she was somehow immune to climate change’s worst effects. “And then you find yourself hauling water in buckets from a creek so you can flush your toilets once a day.”

So yes, it’s been surreal. But her eyes are wide open now. “They say that this is a once in a 1000 years event. But it seems like 1000 years are getting a lot shorter.”

The company doesn’t plan to re-open La Bodega until tourism comes back to Asheville, which may not be for another year, and with revenue this quarter down 60 or 70%, Katie is worried about the financial impact. Still, she’s cautiously confident that her business will survive. “The first night we reopened, all the locals came out. To see our community together, eating and drinking–even on paper plates–I don’t think there’s anything more healing for a restaurant.”

To attend a fundraising dinner for Valencia, host your own, or make a donation, go to Desde Valencia Para Valencia

Donations to World Central Kitchen, which helps communities in need in Asheville, Valencia, and around the world, can be made here

ACADEMY ALUMNI

5(ish) Questions with Harriet Tomlinson

MAD alum and cook Harriet Tomlinson was at the top of her game in her dream job, managing front-of-house at the award-winning Melbourne restaurant Manzé. Then, almost from one day to next, she burnt out—and hard, prompting her to leave the city and embrace a slower lifestyle in the small coastal town of Kennett River. This month, Harriet shares how MAD Academy helped fix her “wobbly compass” and talks about finding a renewed sense of purpose as the caretaker of 180 acres of pristine Victorian farmland and forest.

How did you hear about Academy and what motivated you to come?

I was working with a chef in Melbourne, and he got the scholarship to go over and do the Leadership & Business course. He was a bit further along in his career than me, and I was just in complete awe, thinking it was the coolest thing ever. As soon as I saw the Environment & Sustainability program, I knew it was exactly where I wanted to go. At the time, I’d also just moved out of the city after I’d gone through a massive bout of burnout, which it seems like everybody in hospitality goes through at some point. So, it seemed like the perfect timing — I was in a new town with more time, space, and bandwidth for something new.

WHAT WE’VE BEEN UP TO

Glion Institute x MAD Academy

Last week, MAD Academy hosted a half-day workshop on hospitality innovation for students from the Glion Institute at Restaurant BAEST. Our team explored how Nordic trends are shaking up the sector, showcasing local practices that are redefining industry standards. Joined by Lorenzo Tirelli and Bram Kerkhof from Reduced, alongside Maximillian Bogenmann and Christian Bach from Endless—two Copenhagen-based FoodTech innovators—students gained insights into the future of hospitality and emerging sustainable practices reshaping the gastronomy landscape.

MAD Symposium

Don’t forget—ticket applications for MAD7: Build to Last are now open and you can apply right here. Why do you have to apply for a ticket? Because even a giant circus tent has its limits. We unfortunately don’t have room for everyone who wants to attend, so we use the application to make sure we get an engaged audience made up of a mix of people from different backgrounds and at different points in their career. Make sure to apply by January 9, 2025!

And just a reminder: we’ll be on vacation in early January 2025 — we’ll be back with our regular scheduled programming on the first Monday of February. Happy holidays! ✨